Gene Therapy

The Promise of Gene Therapy

|

|

By Sharon Reynolds

UT Southwestern’s new gene therapy program has the potential to revolutionize medicine in the prevention and treatment of human disease. Gene therapy holds promise for permanently correcting many genetic diseases, which would transform treatment options for stopping disease progression.

UT Southwestern’s program is unique within the United States for bringing together top researchers in gene therapy, expert clinicians in an affiliated pediatric clinical program, and a manufacturing facility on campus where replacement genes will be developed. Although this program currently offers the most hope for children with single-gene rare diseases, success in the science of single-gene therapy potentially could lay the foundation for future gene editing of common brain conditions – from epilepsy to autism – involving multiple genes that are either mutated or missing.

Our vision is that UT Southwestern will become known around the world as the place where children and their families come for lifesaving treatments for rare neurological disorders

|

Providing hope, one disease at a time

As a pediatric neurologist, Dr. Berge Minassian has spent more than 20 years diagnosing children with deadly, rare brain diseases. These conditions cannot be treated, and once progression sets in, most children die within a few years.

“In pediatric neurology, we now know that the cause of many rare diseases is a single gene that’s missing,” said Dr. Minassian, a Professor of Pediatrics, Neurology and Neurotherapeutics, and Neuroscience. “As doctors, we can diagnose the disease easily and identify the missing gene function, but we have nothing to offer these children and families in terms of treatment or cure.”

Drs. Minassian and Gray

In 2017, he joined the faculty at UT Southwestern, where he plans to spend the remainder of his career offering children another option – gene therapy treatment and a possible opportunity to live and pursue their dreams.

As Chief of the Division of Child Neurology at UTSW and a faculty member in the Children’s Medical Center Research Institute at UT Southwestern, Dr. Minassian works closely with his scientific partner, Dr. Steven Gray. Dr. Gray is an Associate Professor of Pediatrics, Molecular Biology, Neurology and Neurotherapeutics, and he is also a member of the Eugene McDermott Center for Human Growth and Development. An innovator in gene therapy, Dr. Gray came to UTSW in 2018 to help build a gene therapy center and bring transformational change to children with rare brain diseases. Before arriving on campus, Dr. Gray pioneered a successful gene therapy clinical trial for a rare pediatric brain disease called giant axonal neuropathy (GAN). The disease leads to loss of body movement and mental function and, ultimately, to death.

Together, Drs. Minassian and Gray are on a mission of hope to develop clinical trials by customizing the same approach used for GAN treatment for hundreds of single-gene diseases – one by one.

“Everything I’m doing at UT Southwestern started with GAN,” said Dr. Gray. “It was driven by families’ hope to save the lives of their children born with GAN. For me, it started with a girl name Hannah, who is the namesake of Hannah’s Hope Fund. We’ve treated 11 children with GAN through the clinical trial, one of whom was Hannah.”

Before a pharmaceutical company will begin drug development for a rare brain disease, it requires scientists to perform extensive preclinical research to minimize risk for clinical trial participants. Dr. Gray’s lab is currently performing preclinical research on multiple rare brain diseases aimed at leading to disease-specific clinical trials and groundbreaking new treatments.

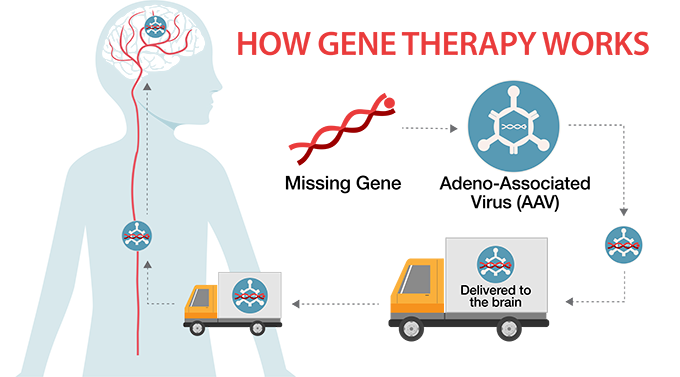

After identifying a rare brain disease and its missing gene, Dr. Gray’s team performs preclinical experiments in mice lacking that particular gene. Once they are able to assess the effectiveness and safety of the treatment in mice, Dr. Gray designs and builds a harmless adeno-associated virus (AAV) called a “viral vector” to deliver a healthy version of the gene to the patient’s brain. The next step would be to seek approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to initiate a clinical trial in humans, and, if granted, treatments are then available to others with the same disease.

In searching for cures, time is of the essence. While children born with rare brain diseases may initially seem healthy and vibrant, they slowly begin to lose body function and abilities as the diseases progress. An important goal of gene therapy is to get children enrolled into clinical trials as early after diagnosis as possible, in order to stop disease progression.

Dr. Gray said, “If successful, children and families afflicted with these terrible diseases will no longer be told, ‘There is nothing I can do for you;’ instead doctors will be able to say, ‘SURF1 deficiency? OK, here’s what we’re going to do.’”

In gene therapy, a missing, healthy gene is loaded onto an AAV that delivers it to the brain. This special delivery system gets the missing gene passed through the blood-brain barrier, which serves as a protective shield controlling what gets into the brain and what does not.

UTSW viral vector manufacturing facility

Purchasing viral vectors for scientific use is a long and expensive process. Vectors are in great demand by pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies and other universities, and few specialized production facilities exist in the U.S. Scientists can spend many months waiting for a vector to be developed. For families in a race against time to save their children, many months of waiting could mean the difference between life and death.

Dr. Gray will oversee UTSW’s new viral vector manufacturing facility, which is scheduled to be up and running by the summer. According to Dr. Gray, UT Southwestern leadership is deeply committed to establishing a world-renowned gene therapy center, adding that his team will produce the highest grade vectors required for gene therapy in humans. He also noted that in-house vector production is faster and less expensive than purchasing vectors through outside facilities, ultimately resulting in more lives saved.

“UT Southwestern’s gene therapy program will enable groundbreaking advances in a new paradigm for the treatment of devastating diseases,” said Dr. Daniel K. Podolsky, President of UT Southwestern. “Philanthropy will make it possible for UTSW to be at the vanguard of gene therapy research and the development of lifesaving treatments of rare brain diseases. Our current efforts are focused on laying the groundwork for this progress. For children with rapidly advancing rare diseases, these treatment advances can’t come soon enough.”

Rare diseases - a large but hidden problem

|

|

Rare diseases can be difficult to identify – and sometimes take years to even diagnose. Half of rare disease patients are children. The diseases often start in an otherwise healthy child, leaving families devastated by the news that their child suddenly faces a terrifying future that can include uncontrollable seizures, loss of motor function, dementia, or a shortened lifespan. There may be limited or no treatment options for the disease, and families can feel isolated and alone in their search for answers. Here are some statistics:

• There are more than 7,000 rare diseases. (Diseases are defined as rare when they affect fewer than 200,000 people.)

• 1 in 12 people will have a rare disease in their lifetime.

• 50% of rare disease patients are children.

• 30% of those children don’t live to see their fifth birthday.

• 80 percent of rare diseases are genetic.

• Less than 5 percent of these diseases have FDA-approved treatments.

Source: NIH/NCATS and Global Genes

|

Families unite to save their children

The Hann Family (from left): Joseph, Gina, Matthew, Mary, Sarah, and Matt

In March 2017, 5-year-old Joseph Hann was diagnosed with a rare form of Batten disease, a fatal, incurable disorder of the nervous system. The disease is a combination of blindness, epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease, and its progression is fast-paced. Doctors advised his parents, Gina and Matt Hann, to make end-of-life plans for their son.

What happened next is a story that the Hanns are happy to tell – over and over – so that no other family will ever hear those words again.

Fueled by love for their precious son, they began searching for any measure of hope from scientists, doctors, and families. They learned about an innovative gene therapy research program being developed at UT Southwestern, working towards clinical use to halt the progression of rare brain diseases.

The Hanns committed themselves to raising millions of dollars to fund research that they hoped would lead to a clinical trial for Joseph’s particular form of Batten disease. Wasting no time, they moved to Dallas in 2017 and began fundraising through their new nonprofit organization, Batten Hope.

“We don’t know if we’ll have the treatment in time to save our son’s life,” Mrs. Hann said. “But if not Joseph, we may be able to save the lives of countless others.”

Guidance and support for families

Dr. Berge Minassian has discovered a great power among families in the rare disease community.

“Imagine if you have a child who’s going to suffer and die. You change completely. Whatever your issues were in life, they all completely disappear and the focus becomes ‘how can I save my child?’ For every rare disease, there are 10, 20, or 100 families – depending on the disease – whose child is going to die. They will find each other and, together, they become a very strong force to advocate for and raise millions of dollars to develop new treatments,” said Dr. Minassian, Professor of Pediatrics, Neurology and Neurotherapeutics, and Neuroscience. He is also Division Chief of Child Neurology and serves on the faculty of the Children’s Medical Center Research Institute at UT Southwestern.

The Hanns have become a guiding light for other families who have come to UTSW in search of gene therapy treatments for their children, and they are committed long term to supporting the gene therapy program.

During a lab tour, Dr. Berge Minassian explains how clinical trials can save children with deadly brain diseases.

“We hope UTSW becomes an epicenter for rare disease treatment,” Mrs. Hann said. “Our vision is to spread awareness so that everyone in the world will know they can turn to UTSW the moment they get a rare disease diagnosis for their child. They will be able to find out the status of available gene therapy clinical trials, and if there isn’t a clinical trial going on for their child’s particular disease, they can find out how to make one happen.”

Mrs. Hann has joined forces with Kasey Woleben to create Rare Dallas, a new nonprofit organization that will serve as a platform to advocate for the rare disease community in Dallas-Fort Worth. Mrs. Woleben’s son, Will, has Leigh syndrome, and she is raising money through her family’s nonprofit organization, Cure SURF1 Foundation, for the development of a clinical trial.

“Kasey and I had an instant bond,” Mrs. Hann said. “We were so excited to talk to each other about where we were on our family’s journey. Kasey said, ‘We have to move this forward for other families.’ It was remarkable for me to meet someone who had the same vision – to change this for others while she was still trying to change it for her own family. The rare disease families all share a bond of ‘We can do this and we have to do it together… and really fast.’ Support makes a huge difference, especially when you’re dealing with the complexities of living through rare disease in addition to all the different components of working and raising a family. The smallest acts of kindness from a community can give hope to families to keep trudging through the really difficult days.”

For the Hann family, each day is a reminder of how precious life is. “When you experience rare disease in your child, you experience the kindness of everyone from teachers to bus drivers to people in the grocery store and teenagers in the community – you see how loving and kind human beings can be. Joseph is pure angelic joy in a 5-year-old boy. For our family, when we wake up every day, we feel like we are fortunate enough to have an angel in our home,” Mrs. Hann said.

Cure SURF1 Foundation works toward

gene therapy trial for Leigh syndrome

|

The Woleben Family (from left): Doug, Lauren, Will, and Kasey

In 2012, Doug and Kasey Woleben welcomed a healthy baby boy into their lives. Will grew into a happy and energetic toddler, but Mrs. Woleben sensed that something was not right when his development slowed and he began to stumble and fall. At age 2, Will was diagnosed with Leigh syndrome, a rare neurodegenerative disease of the central nervous system. At the root of Leigh syndrome is a single defective gene called SURF1. Only a few thousand people worldwide live with Will’s particular genetic mutation.

While the disease is unpredictable, Will is not expected to live past the age of 10. The Wolebens have watched helplessly as their son has lost his ability to walk, talk, and eat.

“Cognitively, Will is a 7-year-old boy who has a sharp mind and knows what’s going on. He is just trapped inside a body that is not working,” Mrs. Woleben said. “His brain is slowly dying. But the part of Will that isn’t dying is his character, personality, and intelligence. He deals with so much, yet he never loses his smile. He’s a sweet, loving, and very smart little boy.”

Through their nonprofit organization, Cure SURF1 Foundation, the Wolebens are leading grassroots efforts to fund the development of a new SURF1 gene that will replace defective genes through gene editing and change the future of Leigh syndrome. A human clinical trial could be ready by 2020.

“The doctors’ expectations are very clear that if Will is not in any condition to take part in this trial, we’ll be raising this money for future generations of children with Leigh syndrome. We accept that. We are incredibly unlucky to have a child with this terminal disease, but incredibly lucky to be a part of this miracle in science, right here in our hometown of Dallas. We hope to prevent other families in the future from going through what we’re going through,” Mr. Woleben said.

As the clock ticks on, the Wolebens try to live each day to its fullest.

“Will is the strongest, bravest little boy and has taught us a lot about life,” Mrs. Woleben said. “He’s my hero, and I’m lucky to be his mom. Every time we see that smile, it just makes it all worthwhile and drives us even harder to keep fighting for awareness and a cure.”

|

To learn how you can support these efforts, contact by Email or call 214-648-2344.

Dr. Minassian holds the Jimmy Elizabeth Westcott Distinguished Chair in Pediatric Neurology.

Dr. Podolsky holds the Philip O’Bryan Montgomery, Jr., M.D. Distinguished Presidential Chair in Academic Administration, and the Doris and Bryan Wildenthal Distinguished Chair in Medical Science.