Couple supports clinical trial to restore feeling after limb loss

Nick Bohac and Jane Smith

By Sharon Reynolds

United through personal tragedies, Jane Smith and Nick Bohac share an extraordinary bond and are a beacon of hope for limb amputees. Nick participated in a six-month clinical trial at UT Southwestern where researchers implanted electrodes in the remaining nerves of his residual limb and sent messages to his brain to generate “feeling” in his prosthetic hand. Jane and her husband, Bud, made a gift to support the next stage of the study and were thrilled to witness its potential impact through Nick’s experience.

Nick’s story

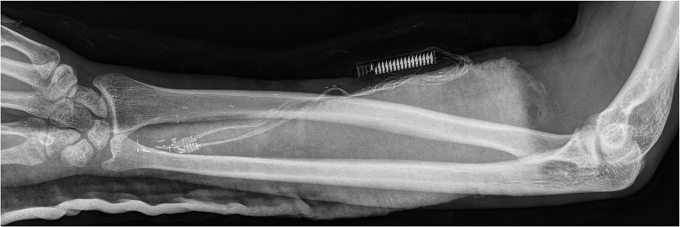

In early 2017, Nick Bohac worked as a foreman in an Austin-area metal shop and was making plans to celebrate his 21st birthday. One morning while training a new employee, his hands were accidentally crushed in a hydraulic brake press. During a more than 12-hour surgery, microsurgeons stitched blood vessels, tendons, and nerves back together and placed metal pins to secure the bones. He woke up surrounded by family and friends.

“I remember feeling angry about losing my brand-new work gloves that I wore for the first time on the day of the accident,” he said. “Someone was trying to spoon feed me. I was batting people away, thinking ‘Just give me the spoon, I can feed myself. I still have three fingers on this side. I’m good.’”

Surgeons eventually amputated four fingers on his left hand and half of his index finger on his right. Since the thumb enables much of the hand’s function, Nick was fortunate that his thumbs were intact. Once he received his robotic hand prosthesis, he was ready to get back to living.

“There’s not really any point in letting yesterday ruin today. I’ve learned that you can either let something like this beat you down, or you can get up and move on. I adapted to it pretty quickly and developed new ways to do everything. Work was stacking up at the shop. Within a week of being out of the hospital, I went in after hours to figure out ways to weld by myself,” he said. Three months post-accident, he returned to work.

In April, Nick joined a new clinical trial for amputees at UTSW that is helping scientists better understand how the nerves remaining within the injured limb can be used to improve the function of prosthetic devices. For several months, Nick commuted weekly to Dallas to spend a full day at UTSW. He also underwent two major surgeries—one to implant electrodes in the nerves within his forearm and one to remove them at the end of the trial.

Thought control to restore movement

Dr. Jonathan Cheng is a plastic surgeon and peripheral nerve specialist at UTSW. He has conducted collaborative research for nearly ten years with Dr. Edward Keefer, a neurobiologist and electrophysiologist, who is the Chief Executive Officer of Nerves Incorporated, a Dallas-based company dedicated to developing solutions for recovery from nerve injury and limb loss.

For this clinical trial, Dr. Keefer is principal investigator and Dr. Cheng is project clinical lead. Along with a talented team of engineers, they have developed methods for restoring touch sensation to an amputee’s prosthetic hand and for enabling the amputee to use the robotic hand much like they used their natural hand before it was amputated. A set of electrodes is implanted in the arm and sends signals into the undamaged nerves remaining in the limb after amputation, evoking vivid sensations within the missing limb. The patterns of signals delivered through the electrodes are the work of Dr. Cynthia Overstreet, a biomedical engineer at Nerves Incorporated who specializes in electrical stimulation of the nervous system.

“As we move forward, our goal is for the robotic hand that replaces the natural native hand to be less like using a tool or an appliance, and to be more like replacing part of the body with something that does the same things,” said Dr. Cheng. “We’ll get closer and closer to that over time as we learn more and the technology gets better. We really feel strongly that being able to feel will have an incredible number of benefits to how people like Nick go about their lives, how they interact using a prosthesis, and what it will mean for their daily living.”

The research at UTSW is unique in that it not only uses the nerves to restore the sensation of feeling, but also allows the patient to control the individual fingers of the prosthetic hand. The cutting-edge neuro-electronics technology and artificial intelligence algorithms that make this possible are developed by Dr. Zhi Yang’s lab in the University of Minnesota Biomedical Engineering Department and Dr. Qi Zhao’s lab in the University of Minnesota Computer Science and Engineering Department. It is the only technology today that can use signals directly from human peripheral nerves to allow free-will, intuitive, dexterous control of prosthetic hands. As a result, this approach has given amputees the ability to control the fingers of a robotic hand naturally using “thought control,” simply by thinking about moving their fingers just as they did with the native hand before their injury.

Nick meets Jane

At the age of 15, Jane Smith lost two limbs after a catastrophic accident. The support from her family and friends helped keep her positive and strong during her recovery.

“My mother told my friends not to do anything for me because I had to learn how to do things for myself. It was the best advice. I was able to get back to doing almost everything, including riding horses and swimming. To this day, I have had a very active, interesting life which includes three children, seven grandchildren, and now seven great-grandchildren.”

Her own experience as an amputee drew her to the work of Dr. Cheng and colleagues. She visited the lab, met Nick, and watched as he participated in several experiments. Through the implanted electrodes, Nick could differentiate between a variety of sensations with his robotic hand. If he touched something with the robotic hand, scientists electrically stimulated the nerves to give him the sensation that his finger was still there and touching something. If he were blindfolded, he might sense someone stroking his absent palm, the hardness of a surface, or the weight of an object.

“When Jane first walked into the room, I didn’t notice that she was an amputee,” Nick said. “I finally realized it when she asked me about designing a walker for her. I came up with an idea to build a one-handed walker to counter her balance issues. She has a great attitude and moves around flawlessly. It is striking to see how well she has adjusted over the years.”

“I was just fascinated,” said Mrs. Smith. “I could tell Nick was an extra-special guy. He is smart and very good at making things and solving problems, which as an amputee is a daily occurrence, and will be for the rest of his life. I know this research will never be able to help me during my lifetime, but it will help future generations.”

Hope for amputees

The Smiths’ gift will support the second stage of the trial that will provide participants with home-based sensory stimulation and provide additional scientific understanding toward a more permanent solution. Nick is thrilled to be part of it all and hopes to participate in the next stage of the study.

“I’ve taken part in the development of something that one day is going to help other people who are in my situation. It’s great to help pave the way into this field,” he said.

Jane adds, “Amputees have a choice. They can choose to sit around and not do anything, or they can make the best of it and do what they need to do to get things done. Sometimes it is challenging, and for the rest of their lives they’ll be figuring out new ways to do things. And that’s also good for the brain.”

Limb loss in America

|

- Almost 2 million people have experienced amputations or were born with limb difference.

- Nick is a partial hand amputee, the most common type of upper-limb amputation.

- Common reasons to lose all or part of an arm or leg include trauma; cancer; and poor blood circulation due to atherosclerosis or diabetes.

- Some amputees have phantom pain where they feel pain in the missing limb.

Source: Amputee Coalition

|